Tsunami is Ned Wenlock’s first graphic novel, but he’s no stranger to the visual storytelling medium. His short form comics have featured in Brent Willis’ Bristol comic, Damon Keen’s comic anthologies Faction, as well as his own mini-comic series Hotpools in the early noughties. Wenlock is also a talented one-stop-shop animation whiz; he has created music videos and short films, and his award-winning 2015 animated short Spring Jam is a delightful film stuffed full of visual gags and gentle humour depicting a young stag’s attempt to attract a mate amongst more impressive suitors.

Tsunami though, offers a darker, bleaker landscape. It explores the tumultuous pre-teen world, through the eyes of Peter, a headstrong 12-year-old trying to navigate the last six weeks of primary school, as he struggles with bullies, his parent’s disintegrating marriage, a burgeoning friendship with Charlie (a self-assured new girl at school), and his dawning sense of self.

Tsunami explores the grappling for identity and belief experienced at that age. That gap between childhood and adulthood when we search for a sense of self, where we stand in the social pecking orders of school, friendship and family life. I recall clearly, at a similar age, trying on different beliefs – for example, that social niceties were fake. The Talking Heads’ lyric ‘say something once, why say it again?’ teased the notion that saying something again was a waste of time and effort, even if others hadn’t heard me the first time. We try on personas and beliefs, and eventually (hopefully) we begin to discover and recognise ourselves.

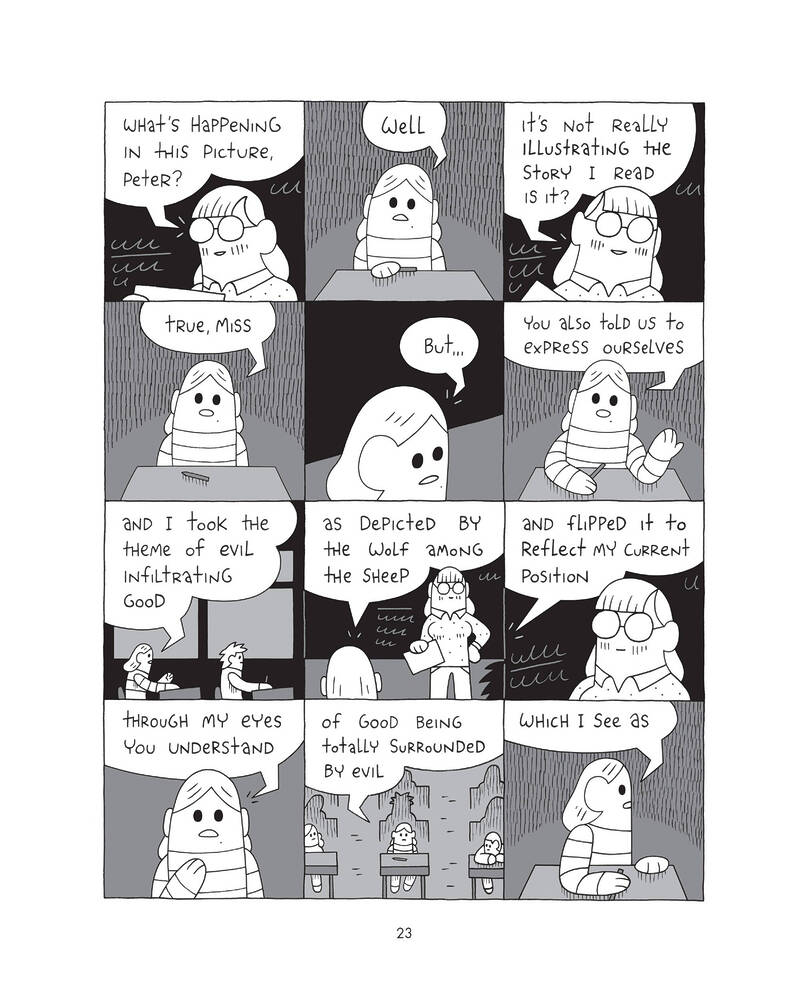

The theme of nature’s savagery runs through Tsunami. Early in the book, Peter’s mother worries to her own mother about his small size: he’s starting high school. She stares into the vast ocean and declares ‘I’m worried he’ll get eaten alive, Mum!’ Elsewhere, Peter depicts himself in a drawing as a sheep surrounded by vicious wolves and explains to his teacher, ‘I took the theme of evil infiltrating good, as depicted by the wolf among the sheep, and flipped it to reflect my current position through my eyes you understand, of good being totally surrounded by evil…’

The adolescent world is presented as a brutal place where nuanced threats, unable or unwilling to be perceived by the adults, take on a life-or-death magnitude to the intended targets. In an early scene, Peter is trapped in his bedroom with his main tormentor, Gus, who gains entry into the house by telling Peter’s grandmother he is Peter’s friend. Behind closed doors, Gus squeezes Peter into unconsciousness, while his grandma happily prepares the night’s beans on toast in the kitchen. In this and other scenes, Wenlock excels at observing the world of adolescents and presenting the layers of complexity in their lives. Peter doesn’t reach out to the adults in his world for help. They’re there on the periphery, ever present, but somehow not of his world anymore. His mother worries about his ability to survive high school, unaware he is already in deep waters.

But despite the heavy content, Tsunami is no grim read. There is a humour which permeates every panel of the comic – both visually and in the writing. Wenlock can tell a good joke. He sets up, and pays off, dialogue and events to hilarious (and devastating) effect throughout the book. The twist at the end of chapter one is brilliant, leaving us with a huge sense of ‘oh no!’ while also letting us know that we’re going to be taken on a journey where things aren’t necessarily as they seem.

Visually, Wenlock has further refined the visual style he has been exploring since (at least) his noughties comics. All the characters are simply drawn, with minimalist linework and character designs which I would describe as Lego-meets-jellybeans. The characters are differentiated by hair colour, hair style, and not much else. There’s something intrinsically funny about the characters’ cartoony appearances. It’s a clever visual language which allows readers to understand the shorthand of which character is which, and to immerse themselves fully into the story.

At times the mix of tension and humour, and the odd-couple relationship between Peter and Charlie reminded me of the protagonists of Charles Foreman’s tragicomedy The End of the F**king World; they’re two misfits (albeit, much younger than Foreman’s teenage protagonists) trying to find themselves in a harsh, confusing world.

At times the mix of tension and humour, and the odd-couple relationship between Peter and Charlie reminded me of the protagonists of Charles Foreman’s tragicomedy The End of the F**king World; they’re two misfits (albeit, much younger than Foreman’s teenage protagonists) trying to find themselves in a harsh, confusing world.

In terms of page compositions, Wenlock relies mostly on a tight, twelve panel-per-page grid. Careful use of some larger panels and the odd (breathtaking) splash page allow enough variation in pacing to effortlessly carry the story. The mostly uniform panels create a stilted reading experience which mirrors the awkwardness of adolescence. It’s all very deliberately anti-excitement. Even the action scenes – Peter being chased by the bullies through streets and forests, fight scenes – are a world away from the dynamic action of mainstream superhero comics. But maybe this is part of Wenlock’s message; evil is mundane, every day. It’s present in actions large and small, and in words – quiet, loud, and unspoken.

As the title suggests, the threat of an unseen, approaching tsunami is ever-present and ever-building. Starting in the first chapter, with a misunderstanding over a fifty-dollar note, we feel that with every wrong decision, with every miscommunication, a sense of impending violent disaster grows.

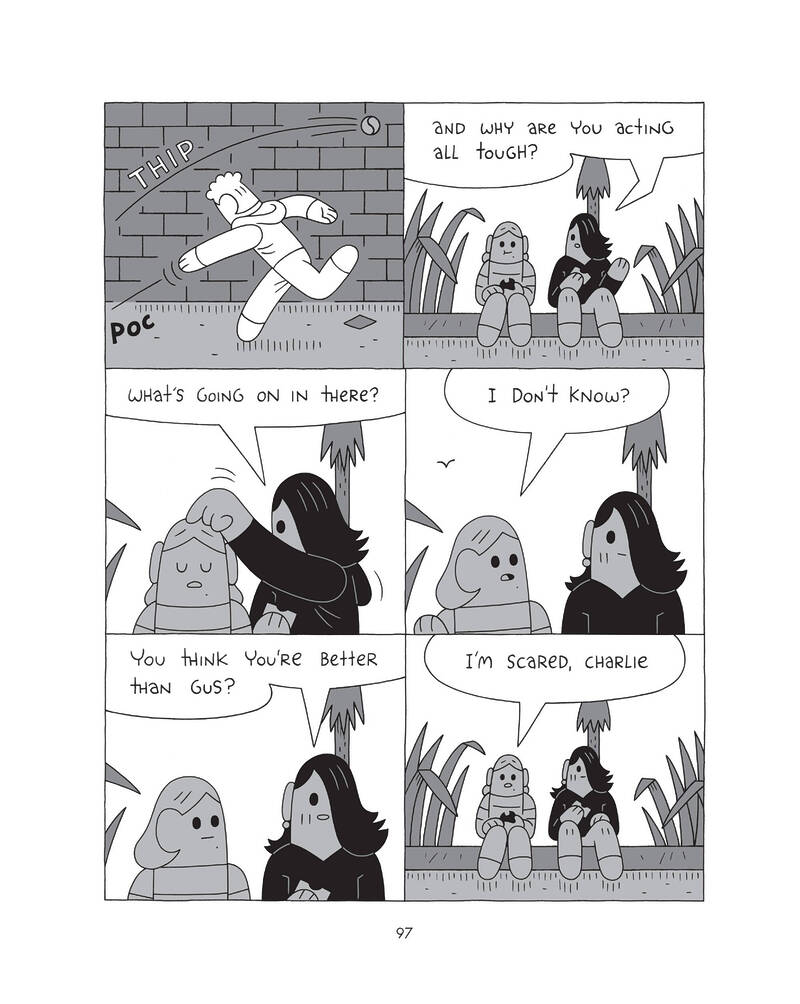

By book’s end I wondered about the nature of Peter. Was he the wolf in sheep’s clothing all along? There are signs scattered throughout the book – Peter eyeing hunting knives in a shop window, the other kids calling him a ‘weirdo’, new-best-friend Charlie asking him ‘where are your friends?’ when she notices she has never seen him with anyone else. In one poignant scene, Charlie taps Peter on the head and asks ‘What’s going on in there?’ and Peter can only reply ‘I don’t know?’ He’s as much an enigma to Charlie as he is to himself.

The final image of Peter lingers in the mind. It’s sad, ambiguous. What happens next is up to our imaginations. We want to tap Peter on the head and ask what’s going on in there. But I think by story’s end, even Peter still doesn’t know.