I remember listening to a Radio New Zealand review of Tusiata Avia’s third book, Fale Aitu/Spirit House. The reviewer, a well-known Pākehā male poet, said the word ‘dark’ over and over again. That adjective ‘dark’, and its mantra-like repetition, undermined what was otherwise a strong review of Avia’s poetry – her array of technical skill, assuredness of voice, the way she tackled issues with vivid, tensely packed language, and so on. But it was ‘dark’. Fale Aitu hadn’t struck me – a fellow Pacific Island woman poet – as especially ‘dark’, irrevocably ‘dark’, indulgently, provocatively, ridiculously ‘dark’. It is life. Our lives. As experienced from within the body of a brown woman growing up in a ‘post’ colonial Aotearoa New Zealand.

In case any other critics leap on the ‘dark’ bandwagon for her latest collection, The Savage Coloniser Book, Avia wants to help. The first line of the final poem, titled ‘Some Notes for Critics’, reads: ‘Yeah, sometimes my poems are dark’. It’s hilarious, an example of Avia’s characteristic knowing, sideways glance, like one of those kitsch dusky-maiden velvet paintings, or her Carmen Miranda-esque author photo at the back of the book where her hair holds the entire world, or the contents of her bedroom.

Rather than dark, this book is knowing. There’s a sophisticated knowing beneath the poems – the ‘fuck-you-James Cook’ type of poems; the ‘let’s-go-there-with-Jacinda’ poems; the ‘who’s-the-real-terrorists here’ poems. This stunner of a collection explores the savage in, around, behind, and before us – in a way I haven’t yet read articulated to this degree, with this much poetic aplomb. We know each other, this collection reminds us. We’re a small island, and poetry atolls are all connected beneath the surface, even if the water keeps rising.

The Savage Coloniser Book is divided into three parts by the symbol of the malu. This is the tattooed mark that appears on the most painful and sensitive part of a woman’s leg – the back of her knee. In Samoan symbology, the diamond shape symbolizes protection. In Avia’s lexicon, the malu serves as a portal to other worlds.

Part One is written in a number of voices, both the savage and the coloniser. There are found poems from speeches made by Tame Iti, Martin Luther King, Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, the ancestors of the policeman who lynched George Floyd, Ahmed Fareed (a survivor of the Christchurch massacre), and of our Teine Sa, Samoan spirit women. The first poem in the collection is the ‘Savage Coloniser Pantoum’, where the split title visually creates two poems on the page. This is a call and response poem where subtle shifts in meaning throughout the repeated lines create a prism effect on the topic of colonisation as the ultimate ‘dumb game’. Its sardonic effect is again, hilarious, Avia’s way of easing you into a collection of politically astute poems that call out savage oppression and racism. These poetic snapshots range from casual, interpersonal microaggressions to political, systemic, and global racism, like Australia’s human rights infringements from their treatment of Aboriginal First Nations Peoples to Manus Island refugees, to America’s Black Lives Matter movement, to the Christchurch massacre, to Auckland’s Ihumātao land occupation.

In Part Two we move from the body politic to the body personal, exploring sex, seizures, relationships with others, and the self (the ‘Jealousy’ sequences are particularly hard-hitting). We read about the body in performance and ritual in poems on FafSwag, our newest Arts Laureates, a Queer Pacific Arts collective invested in social change (a thematic first, perhaps?). We experience the body of the poem on the page in shape poems that wonder: what if the gender roles in myths surrounding Samoan tattooing practices were reversed? What if the women, not men, received the pe’a, the male tattoo? The following poems, ‘Blacking out the Va (ii)’ and ‘Blacking out the Va (iii)’ face each other and in the Va (the interrelational spaces between) visually evoke the pe’a on the page.

Part Three mixes the personal and the political, beginning with ‘Covid in the time of Primeminiscinda’ and an exploration of the internal and external transmission of communicable dis-eases. Avia explores the paradoxical situation of a global pandemic that forces us to experience life in smaller and tighter spaces: from globe to country to town to home to mind with sardonic assonantal-driven humour: ‘Jacinda has become my Krishna / Hare Jacinda / Rama Primeminiscinda’.

The entire book serves as a poetic record of historic reasons for group anger, a useful backdrop for poems like ‘How to be in a room full of white people’, a poem that acerbically ‘outs’ white people. The instances of white-splaining are familiar, provocative and strangely refreshing to finally see in print:

Watchwhite people startle when you use the words white

people together

Listento white people tell you they don’t like being lumped

together like that

Watchwhite people when black and brown people are killed

again because they are black and brown people

Hearwhite people say: It’s hard to be white too

Listento white people say: I feel culturally unsafe

Listento white people say: I’m a woman of colour, white’s a colour

That last line was said by MP Judith Collins.

The pacing throughout the collection is effective as Avia takes us to the edge with poetic and layered diatribes against colonial exploitation and white terrorist massacres, then turns the thematic corner to sex and death: death by seizure, death by abortion, death by a thousand micro-racist papercuts.

Heavy – or ‘dark’ – themes that might overwhelm the more ‘delicate’ reader are carried by an assured lightness of voice that serves as a counter tone to its subject treatment. This voice is casual, and ‘of the people’ – not in a homogenous way, but in a specific, nuanced, multifaceted, strategically essentialist ‘of the people’ and even ‘of the land’ way. We lurch between savage, savaged, colonised and coloniser. ‘Fucking St Barbara (i)’ is written in the voice of the land and seabed being rape-mined. Four poems later we’re in the head of Derek Chauvin, the white police officer responsible for the death of George Floyd: ‘I’m looking straight into the camera … I’m holding my knee on his neck’.

The variation in use of language and tone makes for a rich reading experience. From the encoded and culturally nuanced ‘Ma’i maliu’, the Samoan phrase for ‘seizure’ (literally meaning ‘death sickness’), to the bald profanities as in ‘250th anniversary of James Cook’s arrival in New Zealand’: ‘Hey James / yeah, you / in the white wig / in that big Endeavour / sailing the blue, blue water / like a big arsehole / FUCK YOU, BITCH.’ I’m not sure whether keeping the full expletive over more sanitised versions (F-k) rings the death knell for this book’s admission into school libraries, but if we can trust the nature of contraband, it will find its way into teen hands somehow and in some form.

Of things ‘dark’, of things unpretty, of pain, of red-black anger and wounds, Joy Harjo, the first First Nations US Poet Laureate says: ‘Poetry gives us a way to speak, a way to express our thoughts so we can find pathways to healing. Healing is not always a pretty thing. You have to go through the wound, sometimes you have to go back (through) several times’.

The Savage Coloniser Book poetically documents our wounds, and by doing this provides poetic catharsis. Avia goes through the wound – colonisation, slavery, genocide and racism – and back through it several times. It’s an uncomfortable read in many places. Some might avert their eyes, refuse to lift off their own bandages to see, but it’s a wound that belongs to all of us and one shared by people of colour the world over. These are wounds that leak into our day-to-day lives, whether you’re paying in a bookshop or praying in a mosque, whether you are having coffee with blithely racist friends or standing in a protest line.

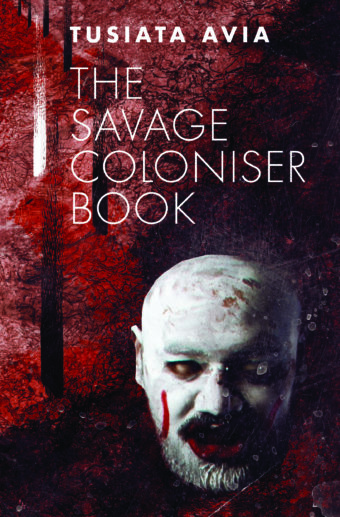

The Savage Coloniser Book is designed to fit in your hand, and like a handbook it offers a poetic guide to colonisation past, present and future, outside, within and beyond us. Avia’s poetic seer’s eye, like the white aitu eyes that stare out from Pati Solomona Tyrell’s cover activation, holds the dark up to the light to heal our wounds.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.