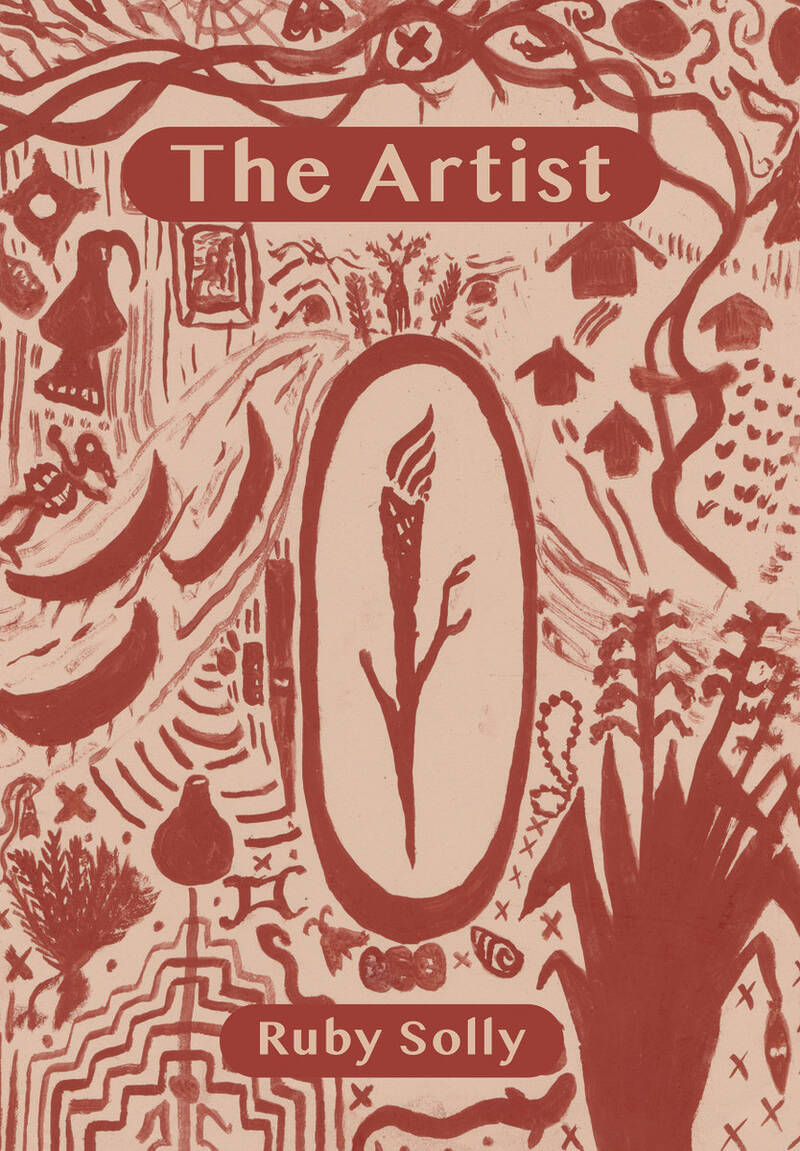

Ruby Solly’s second book is grounded in the pūrākau and cosmogonies of the closely interrelated South Island iwi of Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe, and Kāi Tahu, telling one story through a collection of linked poems. The flow of song throughout serves to braid the kōrero of speakers. The opening lines of the first poem, ‘Sing’, read:

At the start there is nothing but black sand

except it is wider than we can know,

deeper than we can feel.

Although ‘we are not yet a we’, we are ‘the pulse of potential’ within this, and the black sand shifts into ‘a black river’ and then ‘a fiery chain’. I read this as a shifting portal between worlds, and intertwined whakapapa of the largest iwi of Te Wai Pounamu.

Solly is a musician as well as a poet, and here the use of song and musical techniques – such as the ‘ta ta ta’ associated with taonga pūoro and the heart – helps us investigate the implications of a narrative energised by whakapapa. I enjoyed the flow of The Artist, pausing between individual sections and poems, not always grasping the essences, but appreciating the episodic intergenerational nature of the text, reminding me of Vedic texts such as the Bhagavad Gita which also reach into spiritual dimensions and curvilinear histories.

There are antecedents for this approach in the literature of Aotearoa. Keri Hulme’s Moeraki Conversations summons the life-force of the whenua and speaks with both the visible and invisible world. Albert Wendt’s The Adventures of Vela grapples with place and being, situated in genealogies as he voices Vela, spokesperson for the goddess Nafanua. Similarly, there are echoes of other texts in use of godlike chants, imagery of blackness countered by imagery of ahi kā or fire, and the arrivals resulting in encounters that affect whakapapa and agency in this expertly invoked place of standing, tūrakawaewae. Pablo Neruda’s Canto General works on a larger scale, but The Artist has a worlding that is comparable.

In ‘He Ao He Kōpae’, the daughters of Waitaha are each gifted a fan from Hinepūnui o Toka and generate the many winds of agency. (‘Sing us into the wind/says the song.’) In the next poem, we experience the immensity of Rākaihautū as he ‘carved out our landscapes’ with his named tokotoko, Tuhiraki. This act is echoed throughout The Artist with multiple references to forms of writing including tā moko, and art: ‘Feel it flow / from the brush / to the stone.’ (‘Kāti Māmoe’)

Even time is personified here with the arrival of Kāi Tahu:

Tākitimu waka,

Capsized mountains

both here and not here

in this place where time kisses itself

like old lovers finding each other

for the first time.

The arrival of pounamu is deftly painted as a woman bringing knowledge to Kāi Tahu of this taonga:

The woman they call mad,

all tousled hair and wide eyes,

crosses the mountains

with that hard stone, pounamu,

held tight at her breast.

This stone with green water trapped within

the hair cut from Hinepounamu,

here to escape the sandstone woman, Hinehoaka

and her death of one thousand cuts.

(‘Kāi Tahu’)

These accounts evoke ways of knowing grounded in whakapapa. The effect on me is one of letting go of my colonised situation and flying with the poetics because I trust the author’s grounding in tikanga and mātauranga, and their sense of mutual responsibility to the hapū and iwi. Within this indigenous framework of multiple narrative synergies and spirals of whakapapa and ecology, Hinepūnui is a grandmother figure whose name bears the agency of her ancestors. As a young person, Hana – her mokopuna – sang in the caves and was influenced by the art there.

Hana meets Matiu who is captured by her song of the ancestors singing from within his bones. Their love making, bound in the creation chants, results in their gifted twins, Te Heikiki and Reremai. ‘Naming Day,’ a moving tikanga poem, describes their naming by their grandmother.

When their father, Matiu, digs a hole for their whenua with ‘all his mamae, / all his frustration and fear’, I was reminded of Solly’s powerful poem ‘Six Feet for a Single, Eight Feet for a Double’. In that earlier work, another father figure is digging a grave, but where that act is for laying a loved one to rest, The Artist is instead a re-creation. For instance, the baby Aukumea represents the dreaming of babies in the eighth heaven of our cosmology.

Akumea

begins to sing

in an enchanted voice

made of multitudes:

the irirangi, the irewaru,

the voices of the wind sisters too

singing with the celestial choir

distilled down to just one thread.

(‘Kā Kaitapere’)

The resonances with the rangi/raki/heavens continue with an astounding image of the kete of knowledge come undone.

There will be many reviews of this book to come, and these are early days yet for understanding its many gifts. The Artist makes a fine contribution to our literature. It draws on the knowledge base of Te Wai Pounamu. In that sense, it is a tribute to the creations of our ancestors, the many tohu and artworks within the caves and rock shelters both before and during contact with Europeans, but leaps over the perspective of contact to a celebration of our endurance. We are the embodiment of these, and the character of ‘The Artist’ is an embodiment celebrating us:

on top of skin just woken,

the paintings of the Artist

thread lines of fresh-cut rivers

kōkōwai and oil

over her abdomen,

down and out

and through to the ocean

we were fished from.

(‘Awaken; Maniori’)

For readers with an interest in innovative poetry – in New Zealand literature, Indigenous literature, Māori literature – this book is significant and needed. The Artist is an āhuru mōwai, a shelter made from poetry, and is to be celebrated for its craft and heart, and for its whakapapa.