When Kenneth Anger, the American author of 1959 scandal bible Hollywood Babylon, underground experimental filmmaker and follower of influential English occultist Aleister Crowley, died in May, a journalist friend of mine recalled interviewing him during a trip to New Zealand to promote his 1984 Hollywood Babylon sequel.

My friend, familiar with Anger’s ‘Magick Lantern Cycle’ of films, including Lucifer Rising (1972/1980), and the darker recesses of Crowley’s reputation, said he had never been more spooked by an interviewee, going so far as to wear a crucifix for the occasion to ward off evil spirits.

Afterwards, totally unnerved, my friend returned home, where the sense of menace was not alleviated by him finding a light, inexplicable spray of blood specks on the screen of his television. The Devil, like the Lord, moves in mysterious ways. Either that or my friend’s two cats had been sacrificing another sparrow in front of the TV altar. No sign of feathers, though.

Kenneth Anger does not appear in Andrew Paul Wood’s entertaining and enlightening Shadow Worlds: A History of the Occult and Esoteric in New Zealand, but Crowley acolyte Rosaleen ‘Roie’ Norton, whom Anger was researching during his visit, does.

Norton was born in Dunedin in 1917 – during a thunderstorm and ‘with pointed ears, blueish marks on her left knee and a hymenal tag [that] marked her out as a witch from the beginning,’ she said.

‘From age three she was drawing what she called ‘nothing beasts’ – animal-headed ghosts with tentacular arms,’ writes Wood. ‘As a five-year-old she once had a vision of a shining dragon beside her bed. This and other unusual events convinced her from an early age that another, spiritual world existed.’ As well they might.

In 1925, Norton’s family moved to Sydney, where, aged 14, ‘she was expelled from her Anglican girls’ school because her drawings of witches, devils and vampires were thought disruptive’. So, more widely, was the art Norton created, exhibited and published as an adult, including drawings of ‘provocatively nude goddesses and copulating demons’.

If Norton’s art was the start of her tabloid notoriety, allegations that she had officiated at a Satanic Black Mass sealed it, with headlines about her being a devil worshipper and ‘the witch of King’s Cross’. The allegations were made by Anna Karina Hoffman, another New Zealander destined for notoriety, again for witchcraft.

Norton’s own notoriety went stratospheric when one of the Aussie tabloids got hold of (ie nicked) letters to her from Eugene Goossens, the English composer, conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra and director of the New South Wales State Conservatorium of Music. Norton and Goossens had, writes Wood, become lovers ‘in a sort of informal menage à trois’ with Norton’s partner. (What exactly is a formal menage à trois?)

Sample letter content: ‘Contemplating your hermaphrodite organs in the picture nearly made me desert my evening’s work and fly to you by first aerial coven … a delicious orificial tingling that you were about to make your presence felt … I need your physical presence very much, for many reasons. We have many rituals and indulgences to undertake. And I want to take more photos.’

I bet he did.

‘Delicious orificial tingling’ is not a string of words to be easily banished from the mind, but you must try your best.

Goossen’s goose was well and truly cooked when police at Sydney Airport found a stash of 800 pornographic photos in his luggage along with an explicit film and – they were bound to crop up at some point – rubber masks. It was one of the great Australian scandals of the twentieth century and the great Australian classical music one.

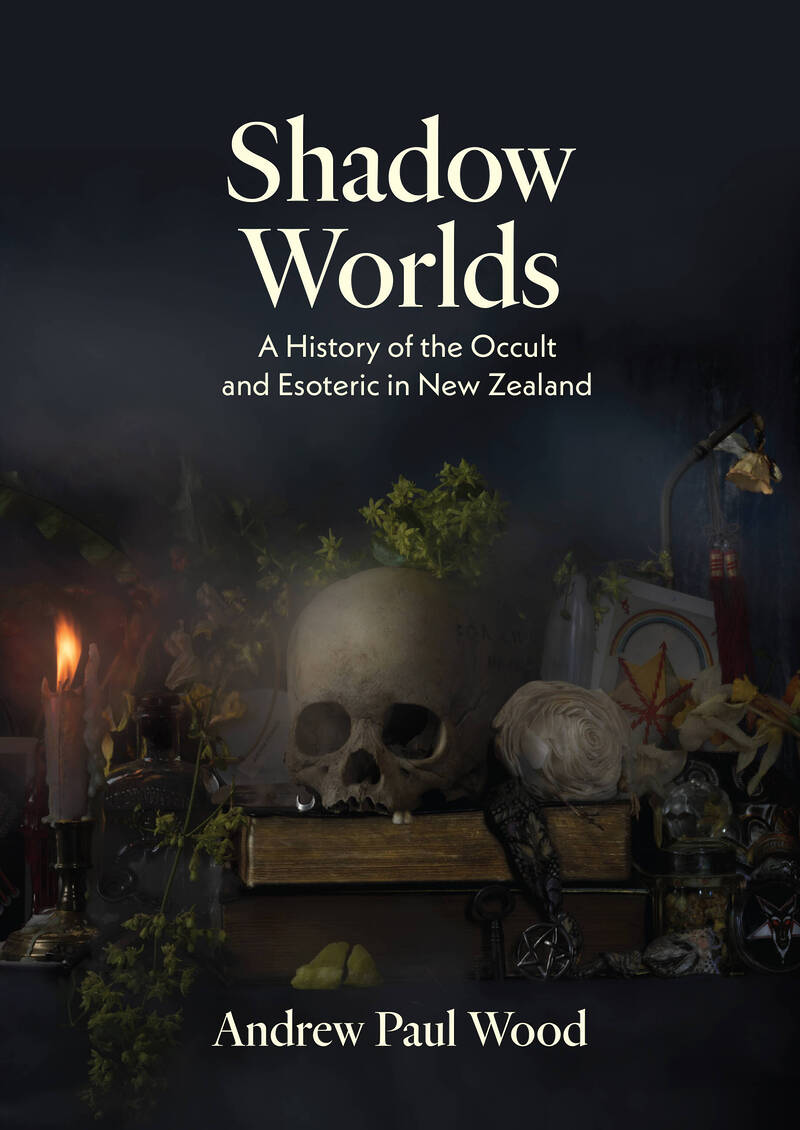

Stories such as Norton’s notwithstanding, Shadow Worlds isn’t much given to the sensational – albeit because there’s not much of the sensational to be given to, but we’ll come to that later. Skull aside, Fiona Pardington’s sumptuous cover art is your clue here: this is a Massey University Press production, not one of those Pan or New English Library paperbacks of the 1970s with covers striving to lure their mostly male punters in with sacrifice-bound blonde beauties, their heaving bosoms barely contained by the plunging necklines of their virginal white robes.

Dennis Wheatley does get a mention and the final chapter (13, of course) is named for his novel The Devil Rides Out. But Wood’s history is a serious, scholarly one; a more lurid writer would have the Devil riding out in Chapter 1.

Serious, scholarly – but not po-faced. Wood is great company as he takes you through these ‘shadow worlds’. His tone is mostly one of tolerant scepticism. Once or twice the sardonic tips into sarcasm. He’s not afraid to call out ‘arrant tosh’ and ‘wowsers’ when he sees them.

This is a book that cites heavyweight intellectuals such as philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer and cultural theorist Theodor Adorno without ever feeling like the sort of book that cites Arthur Schopenhauer and Theodor Adorno. Wood is as ready with his references to TV show Xena: Warrior Princess, industrial music band Throbbing Gristle’s Genesis P-Orridge and writer Bernard Reid’s book Conjurors, Cardsharps and Conmen (recommending the latter for readers looking for a history of the kind of New Zealand magic that Shadow Worlds is most definitely not about).

Wood is a wonderful phrasemaker himself (‘the steady stream of visiting speakers who would hit the quiescent meat of the New Zealand circuit like a caffeinated jolt of Frankenstein’s stolen lightning’; Christchurch’s one-time Temple of Truth ‘is now the site of townhouses knocked up in a tipsy daze of glass-eyed late capitalism’) and has a good eye for the (intentional or otherwise) wonderful phrases of others. You’ll go a long way before finding anything better than Anna Hoffman’s: ‘As the red and black robed magician stepped forward … I caught a whiff of the unmistakable odour of goat.’ Wood relishes a good moniker too (eg ‘the magnificently named Charles Joseph Boneaventure Golder’).

Theosophy, The Golden Dawn, Spiritualism, witchcraft and, yes, eventually, Satanism – Wood maps the labyrinthine relationships and cross-fertilisation of these and many other occult and quasi-occult groups. He is to be admired for his grasp and explanation of the intricate theological differences at stake (no pun intended), of the schisms and splits. The occult and quasi-occult can be as full of factions and in-fighting as the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in the 1920s or your local Lions Club at any time. Their day-to-day doings can be remarkably pedestrian too, be it property problems or (reminiscent of writer Jon Ronson’s gleeful absurdist account of Ku Klux Klan hooded-robe laundering requirements in his 2001 book Them: Adventures with Extremists) other pesky practicalities that intrude on the high camp of earnest ceremony.

For instance, maintaining the Havelock North temple and ‘Vault of the Adepti’ of the Golden Dawn-descended Smaragdum Thalassa: ‘The linen robes creased and required regular starching. Ivy and rainwater would invade the sanctity of the Vault, leading to frequent emergency calls to help bail it out, and possums had a habit of crawling into its ventilation shafts, getting stuck and pungently shuffling off their mortal coils.’

I wonder what Aleister Crowley’s line on possums was.

New Zealanders being, on the whole, a mild people, the groups here have mostly tended towards the quasi end of the occult equation, where the supernatural shades into religion, historical revisionism and political extremism. As Wood notes, there is also a porousness between the occult and science. At times, he draws a long bow, relying on speculation and circumstantial evidence or homing in on the 1970s countercultural theatre troupe Red Mole and even theatrical performance in general.

Pickier readers will have noted that Rosaleen Norton moved to Sydney at a very young age and her story is essentially an Australian one. It is Wood’s misfortune that many of the best stories in Shadow Worlds are as remotely connected to New Zealand: featuring fleeting presences in the country or the overseas backstories to practices before they were taken up here.

There is, however, one strand that is quintessentially New Zealand’s – the relationship between Māori mythology and the occult and quasi-occult. This is a minefield that Wood – a Pākehā – navigates with the requisite delicacy.

Readers shouldn’t open Shadow Worlds expecting to find The Wicker Man in Wainuiomata but the world beyond these shores doesn’t have the complete exclusive on the best stories. Whether a scam or genuinely Spiritualist, the tale of poltergeists in 1880s Greytown is gripping; and that of a 1992 ritualistic killing in neighbouring Carterton (what is it with the Wairarapa?) is bone chilling, involving sex, exorcism, castration, dismemberment, a head being put in a woodburner, arson and the killers ‘standing naked outside on the lawn, chanting in meditation as they waited for a UFO to take them to Australia’.

There is surely a film to be made – or a novel to be written – about the psychic disturbances in mining town Waihi in the 1920s. The appeal is cemented by Wood positing that the ‘disturbances’ might have resulted from repressed anxiety and shame on the part of those experiencing them, Waihi’s inhabitants at the time being strike-breakers who replaced ‘Red Fed’ (New Zealand Federation of Labour) miners in 1912.

Wood’s is a fertile mind and Shadow Worlds is full of intriguing lines of inquiry and thought like this. Once you’ve whiffed it, the unmistakable odour of goat is hard to resist.