There’s not a better description of a penis in all New Zealand literature. A ‘bobbly cock aglint like basted lamb’. Once read, never forgotten. And the image works both ways. Sunday lunch isn’t the same again.

That was from one of Geoff Cochrane’s short stories. But all his writing – whether novels, short stories or, as here, poetry – is, if you’ll forgive me, aglint with such style.

Cochrane, who died aged 71 in 2022, was criminally underappreciated throughout his lifetime. He had his loyal fans – mostly fellow writers, mostly Wellingtonians like himself – but there was little of the wider public acclaim he merited.

As Cochrane’s publicist and fellow Te Herenga Waka University Press writer Kirsten McDougall said in a tribute after his death – and his longtime publisher Fergus Barrowman quotes in his excellent foreword to the poems he has selected – Cochrane was ‘widely ignored by the official givers-out of grants and prizes and invitations to festivals’.

There was a flurry of recompense for this neglect in Cochrane’s later years, with a Janet Frame Prize for Poetry in 2009, the inaugural Nigel Cox Award in 2010 and an Arts Foundation of New Zealand Te Tumu Toi Laureate Award in 2014. But even if Barrowman is too polite or politic to say so himself, I will: it was too little, too late.

Where were the one-on-one Hour Withs at the major – or indeed any – festivals? The rewards such an hour would have brought audiences are evident in writer Damien Wilkins’s 2003 Paris Review-style Sport interview with Cochrane republished in this collection. It is, for my money, one of the great interviews of New Zealand literary journalism. One I had the hapless task of following when I interviewed Cochrane for the New Zealand Listener in 2014. I was on a hiding to nothing.

Where were the truly big prizes? I got an insight into the answer to this when I once suggested to a senior New Zealand poet that Cochrane ought to be a finalist for that year’s national poetry award. I got short shrift and was put in mind of W. Somerset Maugham’s description of himself as being ‘in the very first row of the second-raters’.

Except, for me, Cochrane is in the very first row of New Zealand’s first-raters. I can’t even remember which aridly accomplished book won the poetry award that year, but I remember every one of Cochrane’s collections with both pleasure and astonishment at the heights he scales in them.

For a while, I harboured the hope he would be made New Zealand Poet Laureate. Partly because whose writing had better qualities to celebrate and excite the public’s interest in poetry? And partly, I confess, because I loved the prospect of Cochrane being let loose in the nation’s schools.

Maybe Cochrane was too non-U for New Zealand’s literary establishment. Perhaps in his person, perhaps in his subject matter and the scale of his canvas. But size isn’t everything. Or, rather, something small can still contain multitudes.

Cochrane had been through the mill. He was an alcoholic before he was 20 and didn’t take his last drink until 1989. He was an asthmatic and diabetic. He lived (and died) alone in a cramped council flat in Miramar, Wellington, and, as he described it to me in our interview, maintained ‘a close relationship with the local Winz office’. His teeth were false, his hair was pony-tailed and he wore a beanie. We’re not talking C.K. Stead here.

Whether by nature or circumstances or both, Cochrane was an outsider. But make no mistake, his wasn’t ‘outsider art’. Yes, he wrote about milieux most poets wouldn’t have a clue about (including the demi-monde of his alcoholic 1970s and 80s and the wake of it in which he still lived). But he did so with a panache, erudition and wisdom many of those other poets could only dream of.

Cochrane’s poems teem with life because his life, for all its constraints, teemed with life. Both lived life and read life. He read a lot. His references range widely across high and popular culture. Music and movies as well as books. His vocabulary is virtuosic. But not slackly so; Cochrane uses it in a restrained way. You marvel at the word and where it may have come from, but never doubt it’s the right one in the right place. These poems are disciplined. Cochrane controls their every surprise, their every throw of the reader into an unexpected place or register. He’s a master of the last-line lurch, whether tragic or bathetic. He’s also a master of the repeated line – and the near-repeated line with a one-word adjustment that leaves you reeling or puzzling at the change in meaning. Sometimes it’s just an added comma.

These are poems that stay with you.

I’m not sure if Cochrane should receive thanks or forgiveness for putting the following into the heads of those of us of a certain age ((from ‘Bashō in the Bath’)

He’s no longer young but not yet old.

When he looks in the mirror

he sees scarring and staining,

the sagging of accumulated fats.

What he sees in the mirror

has been too long in the sun

too long in the wind –

too long in the smokehouse of life.

There’s ruin in that face

(gravity being both strong and patient),

but also a sort of overelaboration,

a poofterish embellishment

of indifferent features.

Vanity, thy name is certainly not Geoff Cochrane.

When I transcribed those lines, I mistyped ‘the sagging of accumulated fats’ as ‘the sagging of accumulated fates’, which I flatter myself Cochrane might have liked. As with Harold Pinter, Mark E. Smith of The Fall and an elite group of others, he’s one of those writers who give rise in readers’ lives to ‘found’ moments that could have been lifted directly from the uniquely-his world he created/recorded. For Pinter and Smith, there are social media memes for such moments. Not, alas, for Cochrane. I challenge one of his admirers to start one.

‘Bashō in the Bath’ – from a series named for the seventeenth-century Japanese master of haiku and other forms of poetic simplicity – is as good a showcase as any for Cochrane’s gifts. Some of them, at least. But without these the others would mean little.

There’s the wisdom I spoke of (‘gravity being both strong and patient’). The eye for detail (the ‘scarring and staining’, that ‘sagging of accumulated fats’). The unflinching nature (the ‘ruin in that face’). The precision (the ‘overelaboration’ and ‘embellishment of indifferent features’). The perfectly weighted lines. The economy of it all.

For those of you noting my omission of ‘poofterish’ from the ‘embellishment of indifferent features’, I should add that I do so on my own behalf, not Cochrane’s. His sexuality was ambiguous, fluid even, and he was no homophobe.

I’ve used ‘Bashō in the Bath’ as a showcase but, really, you could open at random any page of this selection and find similar marvels.

In fact, I’ll do so: ‘A sky the texture of peaches / mixes itself like paint’ (‘Postcard’); ‘As swart & lean as soldiers we took on/vodka/acid/Mandrax/tequila/smack / drowned in shallow puddles of neon & oil / conferred with fallen anaesthetists / overdosed suavely in purple bedrooms / jumped in flapping coats from viaducts / discharged our wonky liquorice shotguns / saluted the golden breast of the Lizard King / froze to death in sanctifying snows of white noise’ (‘Zigzags’); ‘And the body of a pupil killed in a car crash / was laid out in the chapel. / And the guy looked most peculiar, / bounced sideways into death, / like some rouged harlot lividly contused. / Like some rash pierrot mauled / by the colours rose and mauve’ (‘Little Bits of Harry’); and on and on.

It’s hard not to finish such poems with a huge grin on your face at all Cochrane achieves in them, at an originality that tells truths we can all recognise. And often because, in his dry, sardonic way, he can be so funny, switching from serious to comic (and vice versa) in a split second.

Yes, Cochrane’s canvas is his equivalent of Jane Austen’s ‘little bit of ivory, two inches wide’ – but, as with Austen, those two inches were sufficient for his needs, and for ours too. The location is invariably Wellington (Miramar, the suburb where Cochrane lived his final years; Island Bay, the suburb where he grew up; the pubs and, later, after the drinking, the cafēs; the weather, always the weather; the occasional trip up the coast to Levin to visit his dying father). There are recurring characters (fellow drinkers, former and otherwise; poet Lindsay Rabbitt). There are recurring themes (the Church, a lapsed Catholic never being entirely lapsed; the alcohol, a recovering alcoholic never being entirely recovered, if only in their dreams; sex, fondly remembered, missed, eventually transcended; death, never to be transcended).

Always present is Cochrane’s preternatural sensory perception, be it sight (‘The wind-minced sea has darkened’), sound (‘Gulls scream jubilance / They know the air is / cooling to a dimness’) or smell (‘There’s a certain chilly moistness in the air. / A whiff of ginger too, / of sugared ginger and wood shavings, / as if an exotic crate / were being unpacked nearby’).

And there’s a humble ambivalence about his writing – its value, whether he was any good, although, as he makes clear in his interview with Wilkins, as he did in his interview with me, he knew he was good (how couldn’t he?) and that it mattered.

I’ve often thought of Cochrane as a miniaturist Karl Ove Knausgārd, his polar-opposite maximalist. The American story writer and essayist Lydia Davis is another touchstone, like Cochrane drawing from the life around her, melding story and poetry to a point where you can’t tell the difference. Proper appreciation of Davis was also a long time coming.

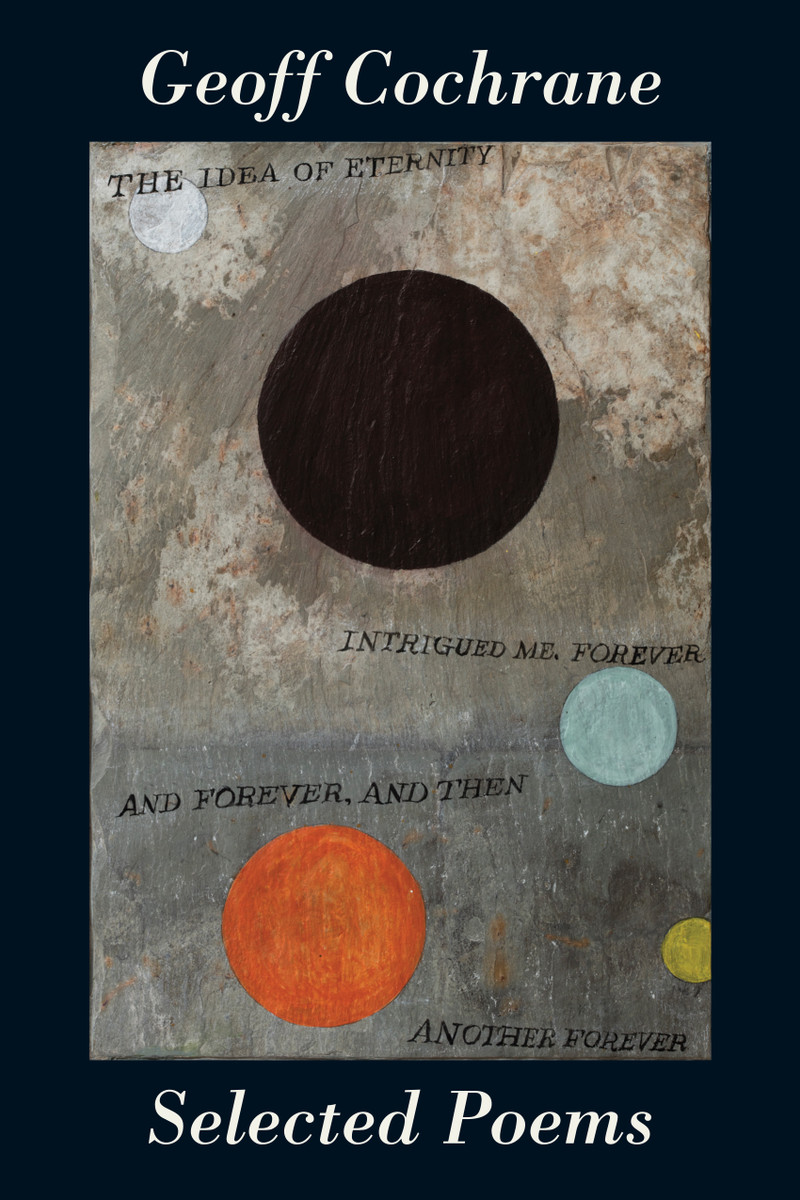

Barrowman is to be applauded for the meticulousness with which he has selected Cochrane’s poems (presented chronologically from 1979–2020) and the luxurious hardback treatment (complete with ribbon bookmark, no less) he has afforded them, including the front cover from a Denis O’Connor painting based on a Cochrane poem.

Cochrane may have been a miniaturist but his ‘two inches wide’ of ivory included his own mind and a mind – especially one like his – can contain a universe.

Besides, like him:

I prefer the short to the long,

the minor to the major. Bartleby to Moby-Dick,

A Portrait of the Artist to Ulysses.

I even prefer the fascinating programme booklet

to the film festival itself.

(from ‘Peninsula’)