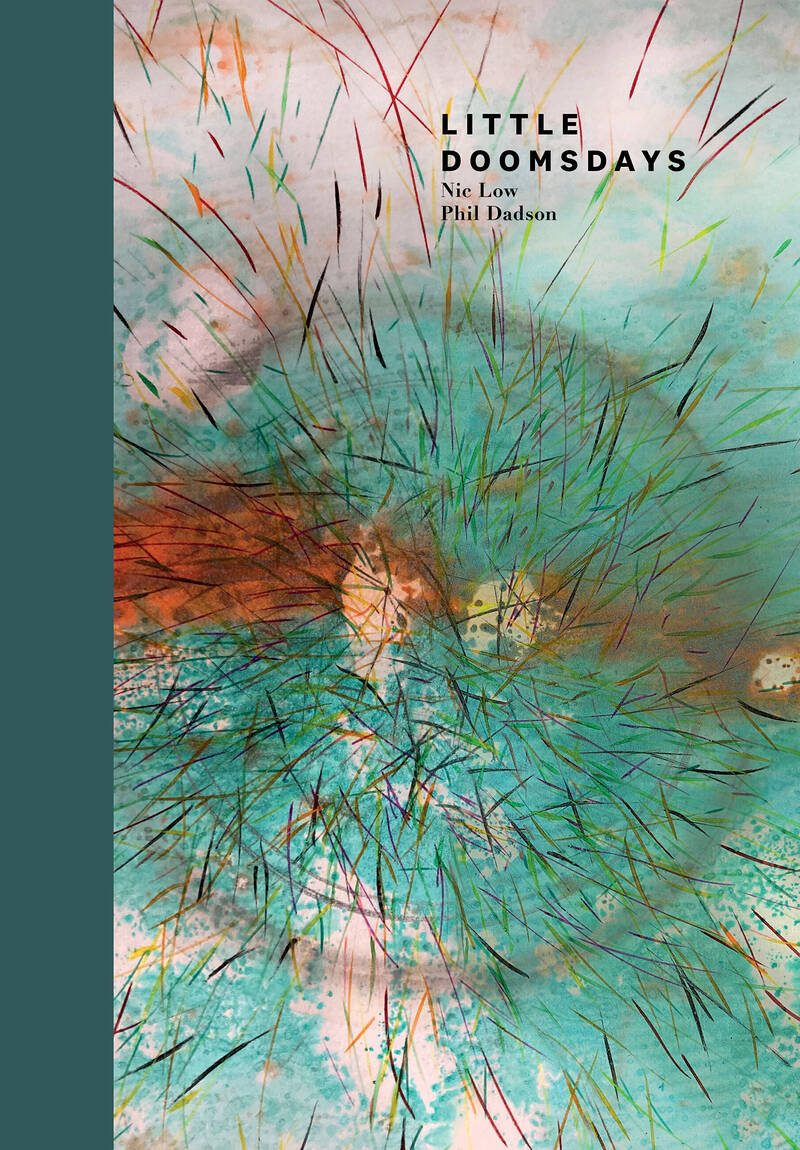

I’m happy to say early that this is one of the most engaging, inventive and original sequences of writing I’ve read in a long time, so congratulations to Nic Low; and to Phil Dadson for his companion graphic work, which navigates variations whose narrative weightings and discourse relationships with the text are subtle, beginning with the book’s front cover – which I’ll return to disingenuously in a while, having read on past it.

The core conceit or concept of the book is ‘arks’, varieties of repositories, stores and archives designed to withstand and outlive catastrophes and even just the passing of time — listed in the book’s opening section as including ‘waka huia, time capsules, caches, burial ships, seed banks, languages, objects and data’. In this account, set in the post-apocalypse future, the overarching or collating ‘ark’ in an ambitious quest for global summary was what became known as the ‘Ark of Arks’, created ‘in the late twentieth century’ by ‘an unstable grouping of scholars, writers and fanatics from several Ngāi Tahu hapū in Murihiku’.

The Ark of Arks, ‘compiled immediately before the last flood’, aimed ‘to catalogue all known arks from the last five millennia’. The scholars ‘gathered their knowledge onto a dozen hard drives and placed them inside a lead-lined stainless-steel waka huia’. We, the readers of the future who have rediscovered the waka huia in the ‘Ark of Arks’, have powered up the screens contained in the ark. ‘You have found the Ark of Arks. You are reading it now.’

We post-apocalypse survivor-readers will find ourselves at, for example, ‘Item 08FDS08S-SF808F: Icarda Dry Area Crop Store, 2012 CE’. We are in Aleppo, in Syria, ‘among the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world’. If we dig down past the cobbles of Mousslama Ben Abdel Malek Street we’ll unearth ‘an earthen time capsule demonstrating how different civilisations will love the same place’ — French, Ottoman, Mongol, early Islamic, Roman, Byzantine, Seleucid folk, to ‘nomads who camped nearby 11,000 years ago’. ‘Old Abraham’ used to milk his sheep nearby.

The ‘Item’ heading directs us to the nearby seedbank of The International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) which would have contained ‘the wild matriarchs of today’s crops, dating back to where ‘the domestication of crops began’. Members of the Free Syrian Army resisting the Assad regime in 2012 found themselves holed up in the ICARDA centre. There, being short of food, the soldiers cooked up ‘a bowl of strange, bitter-tasting chickpeas’.

What you, a reader/viewer of the Ark of Ark’s narrative, will encounter now is the following succinctly poignant conclusion: ‘It was a flavour well known to the people of the Nile Valley — in the time of the pharaohs — that would, once the youngest among [the soldiers] licked his plate clean, be extinct.’ This is good sample of the small, vivid stories that make up Little Doomsdays.

Two images by Phil Dadson accompany the Ark of Ark’s ‘Item 08FDSO8S-SF808F’. The first is an irregularly shaped mottled grey-brown mass covered with variously hued green blobs that become increasingly pale and overcome by the mottled ground; this ‘island’, if we can assume it’s that in one form or another, is surrounded by the grey-brown mass with, running across and up the left side, what could be a dried-out or muddy riverbed — the Tigris post-apocalypse? — that appears to run out into a darker, deeper space. Could the mottled green shapes represent topographically viewed plants such as treetops, or cultivated areas?

If so, the ‘representation’ as it sits alongside Nic Low’s text is at once literal — a ‘dry area’ surrounding zones of cultivation, which would describe much of Syria as we know it — or something more expositional, a narrative of desiccation or its opposite, flooding. The second image on the next turned page is at once obviously literal, a dried leaf shape; but also possibly expositional, the shape of an archived ‘ark’ specimen, or even the leaf-shaped map of a landmass fed by a ‘stem’ of irrigation.

These descriptions are speculative because the images don’t instantly work as illustrations of their facing texts — they expand or open up possibilities, which take me back to the book’s cover image.

In this, a blue-green mass that thins out towards its periphery is entered by an orange shaft and surrounded by an outer ring or expanding shock wave — which is how it seemed to me before reading into the text with its catastrophe premise. The whole picture space contains a cloud of dispersing, thin coloured fragments that seem to be emitted from or caused by whatever is happening within the circular shock wave. The book’s title, Little Doomsdays, does give the reader a broad initial hint. And as we read on, so does the repetition of the refrain, ‘Time is running out.’ A version of the impacting (?) orange mass and expanding (?) shock wave appears towards the end of the book facing its final text on page ninety. The final sentence is, ‘One day we would germinate.’

This reaches back to a poignant section some thirty pages earlier, in which Low is addressing his four-year-old: ‘Ahi, my ark, four years old … what of value can I pass on to you?’ And two pages later, following a double-page spread illustration consisting of multiple overlapping concentric or expanding circles, the following: ‘Our best engineers concluded the only material capable of preserving Aoraki is time, which we have already spent.’ And, in capital letters, ‘TIME IS RUNNING OUT’.

Reaching forward to ‘One day we would germinate’, an arc or circle of linked catastrophe and hope is completed. This final statement is hardly over-optimistic. If anything, it recalls a marvellous earlier ‘Item DSKJ323022: Carved alabaster disk, 2300 BCE’, unearthed from the rubble of ancient Ur. The disk contains the Sumerian Temple Hymns, penned by Enheduanna, priestess of the moon god Nanna. The hymns ‘were sung to the temples, acknowledging those whare as living beings, as we do.’

I read Low and Dadson’s ‘Items’ as time-capsule hymns, sung to the whare/hard drives/lead-lined stainless-steel waka huia, which we potential germinates are fortunate to have as both warnings and records.