A century has now elapsed since New Zealand’s most famous ex-pat, Katherine Mansfield, at only thirty-four years of age, died from a pulmonary haemorrhage brought on by tuberculosis. She left close to a hundred stories (many unpublished during her lifetime), dozens of poems and – because her husband, John Middleton Murry, failed to honour her wish to destroy her personal writings – many letters, journals, and notebooks. Thus commenced a long line of scholars and writers, beginning with Murry himself, who have poured over these remains ever since in order to understand, present, represent, edit, and most importantly, preserve Mansfield’s work for generations of readers.

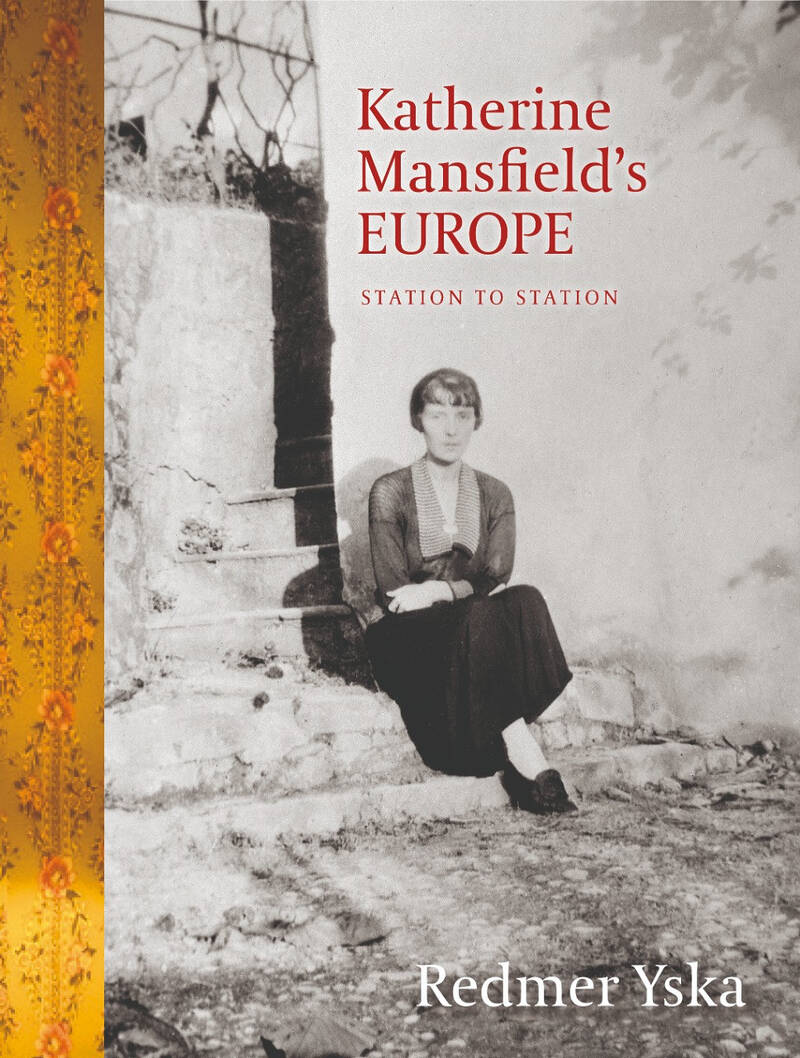

Wellington historian and writer Redmer Yska joins (or re-joins) this group in his Katherine Mansfield’s Europe: Station to Station. His well-received 2017 book, A Strange Beautiful Excitement: Katherine Mansfield’s Wellington 1888-1903, traced Mansfield’s early life in the colonial capital, offering the reader a captivating mix of history, biography, and personal memoir (Yska grew up roaming the same streets as Mansfield). This time, in what feels like a natural progression of his earlier work, he is on the trail of her lesser-known European adventures:

Too little, however, has been written about her European wellheads, the places across the Continent where she lived, was inspired, searched for – and recorded – lost time. Nor have we learned much about her startling celebrity in interwar France, her iron grip on its subconscious. This book addresses these silences.

Yska documents the four years that Mansfield spent in Germany, France, Italy, and Switzerland between 1909 and her death in 1923. Her residence on the Continent was not continuous: she lived an unconventional and peripatetic existence – a month here, several months there, returning to London for increasingly short intervals before again succumbing to the magnetic draw of the mainland. Yska describes her as ‘restless, jumpy even’ and driven by a relentless creative impulse:

Her voyaging deep into Europe never stopped. John Middleton Murry… tried to explain the pull: ‘Once across the English Channel, inspiration will run free, thought be profound and word come back to the speechless’. Mansfield proved him right…

This Romantic association between travel and creativity is echoed in the very nature of Yska’s writing which, although a biography, also takes the form of a travelogue. In it he narrates several trips that he made to Europe between 2017 and 2019 where, as he explains ‘I set out on her rail trails… absorbing and recording what I saw out the carriage window, mostly using her letters and diaries as my maps.’

Yska adopts the same distinctive style of his earlier work in which he alternates his focus between Mansfield and himself, between her past and our present, and between her literary traces and the physical spaces that she inhabited. The reader is often dropped into the middle of a scene: ‘Bernard grins for the camera, pointing up at the blue-and-white enamel street sign for Rue de Tournon’, or ‘There’s a ghostly moon out on this side of Paris, and it’s only three in the afternoon’. The reader is then pulled back in time a full century to ‘The first time Katherine saw Paris…’, or the ‘afternoon of 31 January 1922…’, before being launched forward to the present once again. The dual lens through which Yska operates is both dizzying and compulsive, in many ways reminiscent of Mansfield’s own modernist style with its short sections and frequent changes of pace and perspective.

Likewise, Mansfield’s incomparable skill with metaphor and simile is echoed in Yska’s writing, which includes some superb descriptive passages, such as this one of the billiards room at the Château Belle Vue in Sierre, Switzerland:

At one end looms a fireplace made from a piece of marble so large and preposterously rough-hewn that it is like an iceberg adrift. Extending to the ceiling and edged with lion-topped columns, the marble is mottled like blue vein cheese.

As he visits each of the places that Mansfield stayed in Europe, he imagines what ‘Katherine’ (a one-sided familiarity that seems oddly appropriate) was doing, and thinking, and feeling. This approach leads him to some comic moments that lighten the gravity of the material. He is woken in the middle of the night by a Dominican nun who instructs him to take off his clothes and crouch on the edge of his bed so that she can perform an ‘overbody wash’ – part of the famous water cure at Bad Wörishoffen, a spa town in Germany. This is the same place that a pregnant Mansfield was abandoned by her mother in 1909.

This ranging across genre, across landscape and time-scape, all held together with sharp observation and narrative flair, is quintessential Yska, doing what he does best. He writes this way not because of ego – he never seeks to overshadow Mansfield – but because he is trying to understand her through lived experience.

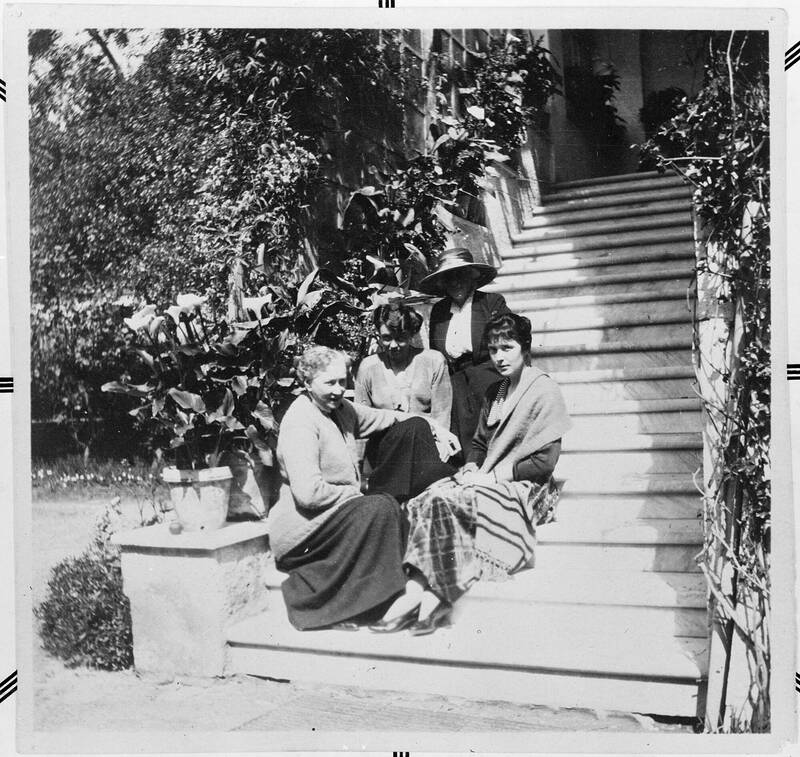

Katherine Mansfield at the Villa Flora, Menton, France. Baker, Ida: Photographs of Mansfield (right) with Connie Beauchamp, Jinnie Fullerton and a friend, Villa Flora, 1920. Katherine Mansfield. Ref: 1/2-011984-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

But can we ever really understand another person from another period? In L.P. Hartley’s novel The Go-Between, we’re told: ‘The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.’ Part of a letter that Mansfield wrote to her mother after observing colonial African soldiers along the Côte d’Azur is shocking to twenty-first century readers, although perhaps unsurprising to readers of colonial-era travel writing. Yska refers to the passage as ‘odious racist invective’, though he notes that it was 1918 and Mansfield was a product of her age. Furthermore, her health was failing fast, and her mood darkening.

Mansfield’s illness and death frame the story and drive the central narrative, hanging over the reader on every page like the damp and gloomy London atmosphere she sought to escape. They also provides the scaffolding for the second story that Yska tells in this book, which is her remarkable afterlife:

I discovered that a company of European ‘foot soldiers’ is ensuring she’s not forgotten. The little-known world of these patient historians, literary sleuths and shameless admirers shaped my understanding of the imprint she left on their respective territories, and how they formally (and informally) commemorate her.

Accompanied by these local experts, Yska discovers monuments, plaques, belvederes, streets, and even a cosy little bar all dedicated to preserving her memory. He shows how Mansfield’s celebrity status in interwar France was in fact the catalyst for New Zealand’s own late recognition and appreciation of Mansfield as an important New Zealand writer. This communion between Mansfield, Yska, the ‘foot soldiers’, and the reader, is enhanced by the book’s lavish production, which includes many stunning photographs, maps, and ephemera, all reproduced on thick, glossy pages.

Mansfield’s words on a commemorative rocher, Fontainebleau Forest. Photo: Conor Horgan.

There is, at times, a tension between the authorial ‘hats’ that Yska wears – he is variously an historian, a biographer, a journalist, a travel writer, and a literary critic. When Yska-the-journalist recounts his meeting with a woman who has an alternative account of Mansfield’s death, the veracity of the story is quickly dispelled and the whole suspenseful episode appears rather pointless. Perhaps Yska-the-historian would have been better to omit the section altogether.

There are also broader methodological questions raised by Yska’s use of the literary sources. In Charlotte Grimshaw’s review of A Strange Beautiful Excitement, she describes Yska’s handling of Mansfield’s characters as ‘a kind of ultra vires: fiction treated as part of historical fact’. What Grimshaw was challenging was the suggestion that Mansfield’s fictional characters had inhabited real life spaces – as if the Kezia of ‘Prelude’ had actually been to Mansfield’s former Karori home, Chesney Wold. A related issue arises in the present book. Take, for example, the following passage:

There’s a moment in ‘Something Childish and Very Natural’ when the male protagonist bellows: ‘“No, I can’t go on being hungry like this.”’ Was this an echo of Katherine’s despair at the aromas emanating from the busy kitchen next door?’

Can we assume Mansfield’s stories reflect how she was feeling or what she was doing at the time she wrote them? Did Mansfield write hunger into her fiction because she herself was hungry? Maybe. But fiction is not a facsimile of historical fact and its use as historical source must be treated carefully. Fortunately, the speculatory aspects of Yska’s work are clearly indicated and do not undermine the impressive scholarship that he otherwise displays. In fact, in other places his blending of genres enables the reader to see an historian at his craft and it is exhilarating to see his archival visits occupying the page rather than being relegated only to the footnotes. It is this experiential and experimental approach to writing Mansfield that is the key to the book’s success.

There still remains the decade or so that Mansfield spent in England, first as a student at Queen’s College in London which she attended as a teenager, and then after 1908, when her father allowed her to return to England. Mansfield never returned New Zealand. While her London literary life is much better known and has been well covered by previous biographers, one suspects that these years would come alive in new and fascinating ways under Yska’s meticulous scrutiny and sensitive guardianship. Could Katherine Mansfield’s Europe: Station to Station be the second part of an eventual trilogy? This reader certainly hopes so.

Katherine Mansfield standing with a parasol by the Villa Isola Bella, Menton, France. Baker, Ida: Photographs of Katherine Mansfield. Ref: 1/2-011912-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand