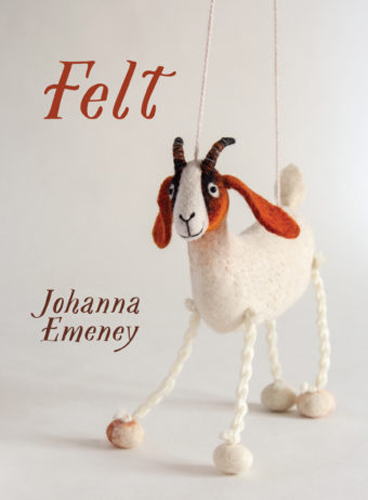

Poetry collections are hard to name. The skill of finding one single word — even better, a single syllabled word — that has multiple resonances and registers is testament to the kind of linguistic craft that lies behind Johanna Emeney’s third poetry collection. This one word, felt, can be tilted and viewed in so many ways and really gets to the heart of the book. These poems are, as the publisher suggests, “concerned with the things that make us feel.”

But they’re also more than that. There is the feeling of the lyric subject, the “I” that speaks and feels throughout these poems. But there is also the empathetic and compassionate observer, looking beyond the self to ask why people feel things the way they do. Or, perhaps, more accurately, what kinds of feelings make people behave in certain ways. This is a landscape of feeling, of what is felt, but by diverging from the singular self — or framing this self in the second person, as Emeney regularly chooses to do — these poems are very rarely self-indulgent. Rather, Emeney traverses affective and emotional worlds of sentient others — people, animals, sometimes plants — with an attention to form, and with an eye to the linguistic details that enable us to engage with and articulate these realms. The poet is listener and guardian, bystander and spokesperson, feeling her way into the feelings that are felt around her. From “Hospital Guard”:

I liked the young guard—his leanness, his untouched acne,

his manner, measured as that of a middle-aged man.

He sat all night and half the morning watching you

indirectly, with neither judgement nor intrusion.

It was simply his duty to defend you against all harms.

The poet observes the guard who, in turn, observes the poem’s subject, the patient whose circumstances for being hospitalized we are not privy to. And while the poet meditates on the young guard’s indirect gaze, the reader is inadvertently left to wonder, what kind of situation is cause for a hospital patient to have a security guard, and who is this patient to the poet’s speaker? There are no answers here. Instead, the poem is concerned with guardianship itself, comparing the young man to his kinsfolk in “large European galleries,” whose job it is to protect the “treasures in their charge” from “greasy pilgrim hands.” It is a distillation, an indirect and undirected reflection on the ways in which people take care of others.

This act of taking care, attending to feelings, is also accounted for in more unequivocal ways throughout the collection. Emeney’s book is populated with animals — goats, ducks, frogs, gulls, dogs, horses — the kind of animals one takes care of (Emeney is herself an animal lover, who lives on a lifestyle block north of Auckland with many of these said beasts). But the book is also peopled with fringe-dwellers and life-sufferers: a woman called Rose who posts her landline when she finds a stray cat (in “Comments Section”); a couple who have been given homework by their therapist “to stand/holding each other/for five minutes” (from “Couples Therapy”); an ex-student of the poet’s speaker currently in Emergency Housing and who is explain via text message the “difference between smack and crack” (from “Favoured Exception”).

In all of these poems there is a deep empathy with the subjects, be they animal or human. There is a sense of feeling towards the other, of reaching out in order to relate or to understand. And, in doing so, the poet is at a slight distance from the centre of the book. In a poem called “That Face,” the opening line reads “I would love a face that doesn’t give itself away too easily,” where the poet covets “those quick, uninvited changes — slip of smile, catch and dart/of eyes, the space between white and colour, silence and quiet.” What I think Ememey is saying here, and elsewhere in the collection, is that she (if the “I” of the poem is in fact Emeney herself) would like to offer the kind of relationality that does not place the self at the centre. That is, that there might be a self that could transcend the scrub and thicket of the ego in order to simply care for a world outside of that self. She observes that in between “white and colour” or “silence and quiet” there might be a space in which one could dwell without the noise of “boastfulness” and hover instead in “kindness and concern.” If we extend this out, it might be taken as a comment on the kinds of social worlds that so often are preoccupied with big, “boastful” colours, the great commotion that is the many individuals jostling for a space to express their unique identities. In Emeney’s work, the personal is not political; rather, the communal — where kindness and concern for the other happens — is a political gesture. It might help us get out of the kind of individualistic funk that several decades of neoliberalism has caused.

Emeney’s poems are written with a deft hand. She has a great handle of the line and form, and uses both the short and longer lyrics to tell stories, expand moments, and elicit feelings in her reader. Admittedly, there are a few occasions in this collection where I felt the pen wobble a little; there were some instances where the poet could have taken the foot off the accelerator a little, where she might have got the reader to that desired place without quite so much effort. But for the most part, most of what makes up this book will go unnoticed. That is, the craft and structure is tight to the point of being largely invisible. Emeney writes a world in these pages where kindness and concern are the currency, where what is felt is the poet’s first language.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.