There is a shared memory among New Zealanders of a certain age, which means those who were at high school in the early-mid 1980s. I was in Auckland, Rebecca Priestley was in Wellington, and both of us were among the thousands who were put onto school buses one afternoon and driven to cinemas to watch an American made-for-TV movie, The Day After, about the effects of a nuclear strike on a midwestern city. It showed ordinary life before the attack, the attack itself and, worst of all, the relatively new idea of the unsurvivable nuclear winter.

Memories of this school trip occasionally surface in online spaces as Gen-Xers start getting nostalgic. There was a recent spate of it when the social media app Threads launched, prompting memories of a much darker British movie of that name from around the same time. But what The Day After showed us, as we sat in the movie theatres in our school uniforms, was that even if the seemingly inevitable war was entirely set in the northern hemisphere with the USSR firing missiles at the US and vice versa, the long winter would reach us all eventually, ‘when particles in the atmosphere would block the sunlight and we’d starve to death because we wouldn’t be able to grow food,’ Priestley writes.

Priestley, who is now a science writer, moves on to an even bleaker account – perhaps the bleakest nuclear story ever told. That is Raymond Biggs’ When the Wind Blows, ‘which innocent children all through the 1980s read’. A nice old British couple named Hilda and Jim survive the nuclear attacks but radiation poisoning makes them ‘progressively more unwell, with headaches, fatigue, vomiting and diarrhoea, hair loss, bleeding gums’. And this quiet horror story was told in cartoons by the guy (Raymond Biggs) who did Fungus the Bogeyman.

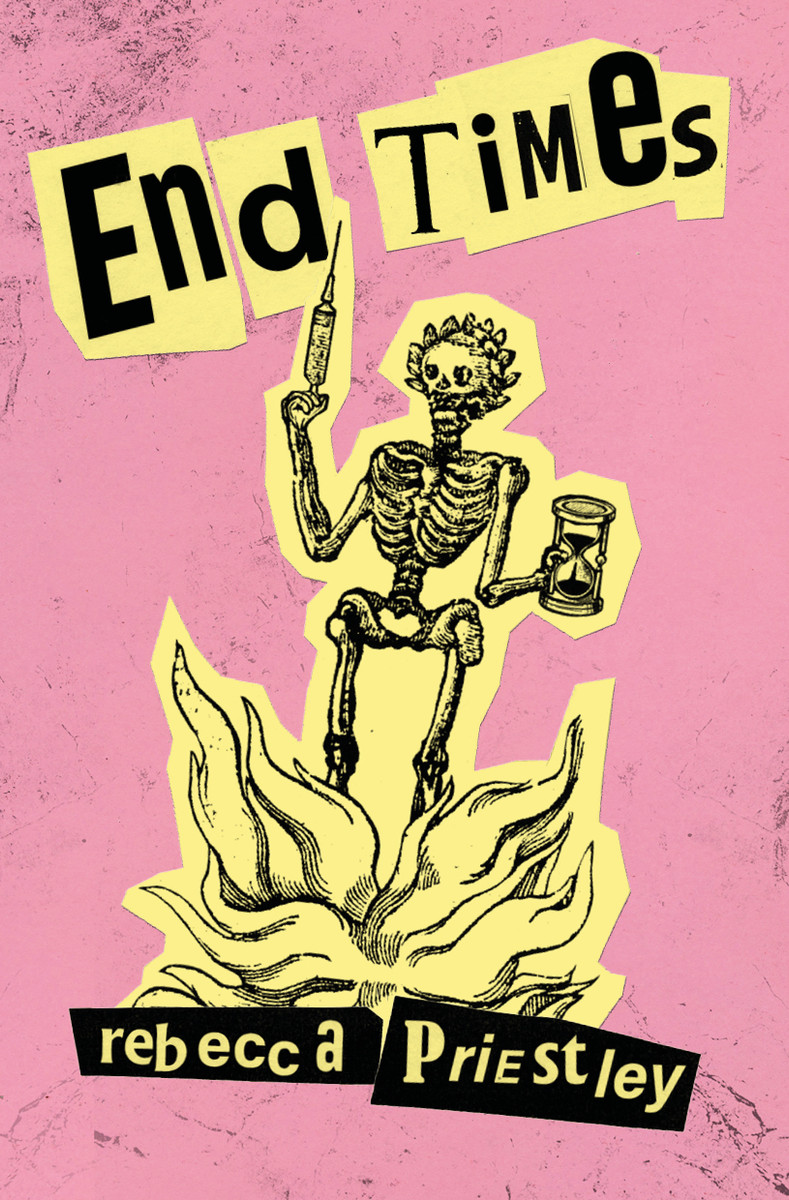

Priestley remembers all this during the years of the Covid-19 pandemic, which made many of us just as isolated as Hilda and Jim and just as fearful. Her book End Times is a mix of essay, travel guide and memoir, constructed around a road trip down the West Coast of the South Island with her BFF, Maz. Friends since they were kids, Maz and Priestley shared formative teenage experiences – they were both briefly punks and, more significantly, born-again Christians. Both seem like they were plausible responses to the 1980s fear of the imminent end, or the shadow of the bomb.

When I heard about this book, I imagined Priestley’s punk experience and her Christian experience were linked, or shared a kind of imaginative intensity or radical oppositionalism. Wellington punk was unusually political – it was anti-war, anti-nuclear, anti-state, anti-racist, anarchist in the proper sense. The antivivisectionist movement was a big part of the capital’s style of punk, as animal rights activist and author Bette Overell, then a woman in her sixties, led packs of mohican-sporting vegetarian punks on marches through the city. Those guys were not mindless thugs.

That isn’t the punk world of Priestley and Maz. They were more like the characters in the film Ghost World, stuck in the boring suburbs and looking, even longing, for an alternative. Life was elsewhere. You could read about it in the NME. They cut their hair short, learned to drink and went looking for the punk world when they caught the train into the city. For a short time, they found it.

But their Christianity lasted longer and made a deeper impression. Priestley’s chapters on her years as a teenage Christian are valuable as a rare account by an insider turned outsider, told with empathy, fairness and non-judgmentalism. As with the punk experience, there is less of a feeling that she engaged with the content of the religion, or the values it offered, than that she was looking for somewhere to belong.

After the singing and the prayer, we felt exhausted but happy. Everything seemed somehow different, like something fundamental had changed inside us; we had been transformed, and something now connected us, at some deep, deep level, with the rest of the Upper Room community. We stood around drinking instant coffee and eating gingernuts. The grey-haired woman came over to us and said, ‘Where’s the Holy Spirit?’

‘Inside me,’ said Maz. I nodded: same.

This was a time when Christianity was galvanised by end times prophecies, the AIDS crisis and opposition to homosexual law reform, and even conspiracy theories about barcodes. They attended church groups on weeknights, they spread the word outside McDonalds in Manners Mall, they went to church camp and, after a while, they moved on, as many teenagers do.

Despite Priestley’s sympathies, and her present-day recognition that ‘there was something real there, something we can’t explain away’, those Christian end-times beliefs seem to her like fantastical distractions when compared to the much more tangible, material end-times beliefs she encounters these days as a science writer, and it’s fitting that the West Coast is the site of the road trip that frames the book. The West Coast is wild, beautiful, sometimes feral, nearly post-apocalyptic. It’s a place that was shaped and ravaged by extractive industries, one where climate change is already having an impact. As a landscape, it’s almost symbolic.

Here she is in Granity, which is literally falling into the sea: ‘I walk until I reach a tumble of broken concrete and mangled reinforcing wire. It’s impossible to tell what it used to be. A sea wall? A pier? Remnants of an earlier civilisation; the concrete and iron age.’

She meets vaccine doubters and, further down the coast, she interviews Bruce Smith, who was then the Westland Mayor. He embodies a hardy, stubborn West Coast common sense that is sceptical about climate change, sceptical about experts and sceptical about being told what to do by ‘Ted at Victoria University or whoever’. There are some positives to this, she acknowledges.

Coasters are famous for being resilient, nonconformist, and they do have a great sense of community. I’d like to be more like that. Maz always says that if something went wrong over here, you’d have ten people with diggers turning up to give you a hand.

If the end of the world comes, you could find yourself in worse places than the West Coast, unless it’s the Alpine Fault that delivers it.

Priestley is a skilled, intelligent writer but she is trying to do a lot in this book and it doesn’t all connect. End Times is both an account of a lasting friendship and a meditation on apocalyptic thinking. It is both a travel story and a midlife memoir. It is impressively accessible science journalism about the Coast and the coming climate crisis. It is also, we come to learn, a book about a kind of anxiety we can never fully appreciate as readers, or whose shape we can never really apprehend. There is end-times anxiety, which is the all-too-common sense that the world must be coming to a close, but there is another anxiety here, one that is more personal and harder to pinpoint and possibly even harder to solve.