In the wake of the Land Wars, Māori seemingly disappear from the national narrative, retiring to what Richard Seddon called ‘to their Native fastnesses’ to get on with the important business of dying out. Nothing could be further from the truth: the post-war period proved to be one of the most vibrant in Māori and indeed New Zealand history. With Imperial military spending maxed out on the colonial credit card, and both sides battle-bruised and war-weary, Māori and Pākehā took up the arduous task of diplomacy and compromise to negotiate what this country would be. A profusion of Māori political movements, many seeded before the wars proper, flourished, navigating multitudinous pathways to an ultimate destination of maintaining rangatiratanga in a colonial landscape.

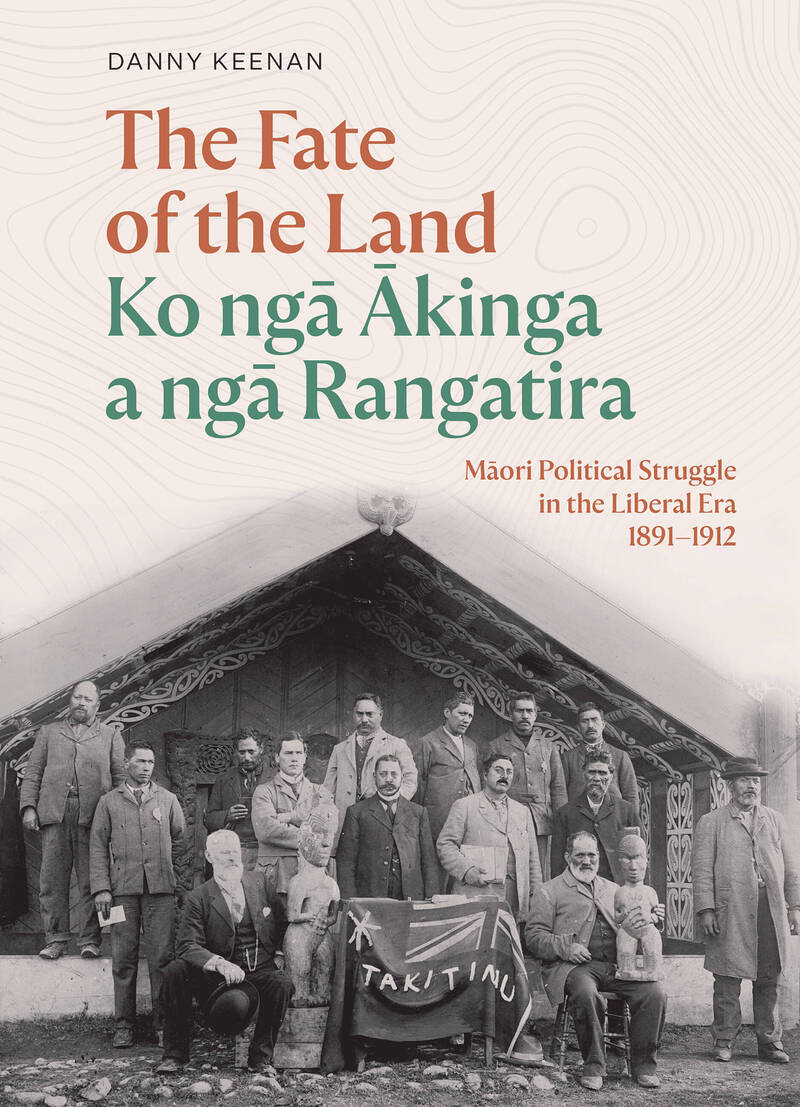

The Fate of the Land by Danny Keenan (Ngāti Te Whiti ki Te Ātiawa) captures the vitality and vigour of this era with a rare confidence and clarity. The book explores the Liberal era of government between 1891 and 1912, focusing on their policies towards Māori and the efforts of rangatira to influence and at times impede Liberal policy. Political history can be drier than a prohibitionist’s party, but this era is crucial. The Liberals were our first political party, rejecting the short-lived ministries and fractious coalitions of the past, and hammering together a range of sectionalist interests into a united political party. The Liberal era saw the rise of stable government, party politics, populist prime ministers and social reforms. This is the origin story of modern New Zealand politics, and of modern New Zealand. It is equally the origin story of modern Māori politics.

The key texts in this area were largely published in the 1960s and 70s; the 1990s saw revisions and insights from Māori authors, and the 2000s saw further detailed studies. This is a hard neighbourhood to hang in: histories of politics, policy and bureaucracy are by their nature complex and difficult to enliven. Older texts make for a difficult read; there is a bifurcation of Liberal and Māori foci; and Māori movements are at times overshadowed by the disappointing outcomes of their efforts.

The Fate of the Land triumphs in its ability to render this period accessible and alive, thanks to the clarity and confidence of Keenan’s writing. He breathes life into rangatira and the formidable movements they led, framing them beyond a single issue or stereotype. Pāora Tūhaere is not simply the outspoken leader of a fishing village concerned about his oysters: here he is a national leader and peace maker, attempting to reconcile old friends King Tāwhiao and George Grey, and building a national movement to establish a Māori parliament. Wiremu Pere is no longer the tired old man of parliament, but a leader who ‘forcefully resisted unrelieved land purchases, speaking fearlessly to Māori and Pākehā alike’.

Te Kotahitanga, a national movement advocating the establishment of an independent Māori parliament, is truly given its due: the startling fact that its 1893 petition for a Māori assembly garnered just three thousand signatures fewer than the suffragettes’ petition of the same year speaks to the silencing of Māori stories. We learn that Prime Ministers John Ballance and Richard Seddon spent much of their careers courting and thwarting Te Kotahitanga, revealing what a formidable movement it was.

The Kīngitanga and successive Māori Kings are presented here as stern, steadfast national leaders far from defeated and done. At an 1879 gathering in Te Kōpua attended by Premier George Grey and welcomed by a descendant of Hongi Hika, King Tāwhiao arrived with 180 bodyguards who ‘marched in slow time’ armed with double-barrel guns, taiaha and pistols, presenting an ‘imposing military parade’ – though it is unclear if the armed guards were to protect the king from Grey or Ngāpuhi. Tāwhiao declared: ‘I have the sole right to conduct matters in my land – from the North Cape to the southern end’.

Many other movements leap from these pages, including the Repudiation movement whose supporters at one gathering were literally ‘roped off from other Māori because of their perceived “radicalism”’, and the Māori suffragettes who campaigned for the right to stand for, vote in and speak in the Māori Parliament, as well as voting in the settler parliament. Keenan describes the flourishing of Māori newspapers dedicated to these social and political movements. This was the world our ancestors built in the wake of the wars.

Smaller moments shine here as well, like Seddon ‘risking life and limb’ to cross ‘a turbulent Lake Waikaremoana in darkness’, and the realisation of Te Aute old boys Āpirana Ngata, Māui Pōmāre and Peter Buck that their ‘dream of galvanising Māori and equipping them for the new world would, it seemed, take longer than the summer holidays’.

Keenan argues that the results were disappointing for Māori. Liberal policy focused on securing and validating the title of lands already purchased by settlers to clear the way for development, to identify and validate Māori title to their lands to allow for sale, and to facilitate the further sale of what they regarded as Māori ‘waste land’. Māori positions were complex: the Kīngitanga wanted a separate region under a Māori monarch; Tūhoe wanted complete independence and were temporarily granted it, with the establishment of New Zealand’s only native reservation in Te Urewera. Kotahitanga wanted a separate Māori parliament to sit alongside the settler parliament. Iwi held a range of views. All advocated the protection and retention of Māori lands, yet land sales were essential to raise capital to develop Māori lands. Māori were playing a dangerous game.

Legislation in 1900 introduced Māori councils to improve sanitation – because ‘there was no point in reserving lands to Māori if they faced extinction caused by infectious diseases’ – and land councils that seemed to offer Māori a degree of control over their lands. But these bore meagre fruits. By 1909 both councils were defunct, and the dream of a Māori parliament lay in tatters. During the Liberal era the government purchased 3.1 million acres of Māori land, while a further half million was purchased directly by Pākehā. Despite their herculean efforts, Māori could not assuage settler hunger for land.

The Fate of the Land does have its shortcomings. As a project started in the 1990s it sidesteps several decades of Māori scholarship and Waitangi Tribunal reports. While some effort is made to include Māori women, they read as a side note, and are too often treated as the mothers and wives of great men, rather than rangatira and political leaders in their own right. A younger generation may struggle to understand why Māui Pōmāre believed there was ‘no hope for the Māori but in the ultimate absorption by the pakeha’, and that in time Māori would be ‘imbued with loyalty and imperialism, proud to be members of the Empire’.

This is a readable and useful book that makes accessible a complex era of our history. The denouement does not diminish the deeds of valiant and visionary rangatira, nor does the story end here. As the recent sparring between the Kīngitanga and Ngāti Whātua near the site of the first Māori Parliament shows, the mana of these ancestors, and their visions for rangatiratanga, live on.